One year after scientists first identified the new coronavirus, several variations of the virus that appear to be more infectious are causing global alarm. Though the new strains are not thought to be more deadly, their spread raises the possibility of overloading already strained health-care systems. Now, countries’ vaccine campaigns are up against the increasingly fast transmission of COVID-19.

What are COVID-19 variants?

Over time, viruses undergo mutations. In the COVID-19 pandemic, scientists around the globe have documented thousands of mutated versions of the coronavirus, called variants or strains. Several of these variants—in the United Kingdom, South Africa, and Nigeria—are being closely monitored by health experts, including at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

What risks do they pose?

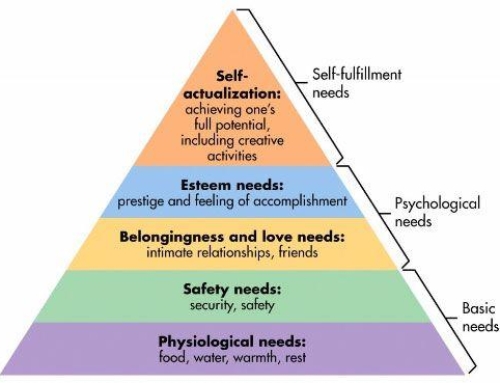

Scientists are particularly concerned about the UK and South African variants because they seem to spread more easily than the original virus. The CDC notes that there is no evidence that they cause more severe illness or increased risk of death. Yet, the transmission of a more infectious variant could spur exponential growth in the number of COVID-19 cases, a dangerous scenario given the challenges some countries have faced starting vaccine distribution.

Such rapid growth in cases could, in turn, lead to more fatalities: with an increase in hospitalizations, health-care systems could become overwhelmed and consequently unable to care for large numbers of people with COVID-19 infections. In many parts of the United States, which is experiencing the world’s most extensive outbreak, intensive care units were already near capacity at the end of 2020. Hospital staff have said they will not be able to maintain high standards of care for patients.

Additional concerns include whether COVID-19 vaccines will be less effective or even totally ineffective against these variants. Experts say the latter is unlikely, and that there is no evidence of this yet, but they are continuing to study the new strains. Also, the head of the German vaccine maker BioNTech has voiced concern that more contagious strains could make so-called herd immunity

more difficult to achieve, because the threshold for sufficient protection in a community depends on the speed with which a virus spreads.

How are countries responding?

Countries where these strains are circulating are taking swift actions to stop their spread, as case levels already appear to be following worrisome trajectories.

In the UK, Prime Minister Boris Johnson announced a new nationwide lockdown due to a surge in cases and hospitalizations. The UK strain has also been detected in more than thirty other countries, including China, India, and the United States, which are closely tracking cases of it. Some U.S. scientists are arguing for a

nationwide surveillance program to spot such cases.

The variant that emerged in South Africa—which currently has the highest rate of new COVID-19 cases of any country in Africa, at more than fifteen thousand per day—has also spread internationally. This has prompted the South African government to tighten its lockdown, and led some countries to ban or restrict travel from South Africa.

Meanwhile, the vaccine rollout continues, though some countries are making quicker progress than others: UK officials are hoping to get out in front of the variant’s spread by vaccinating their most vulnerable residents—totaling about thirteen million—within six weeks, while South Africa doesn’t expect to start vaccinations until the second quarter of 2021.

SOURCE: www.cfr.org